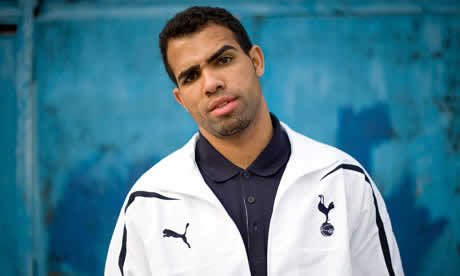

Sandro: 'I told my brother: I'll be the player we should both have been'

Posted Saturday, April 02, 2011 by theguardian.com

The Tottenham midfielder heads for the Real Madrid game driven by a desire to repay his family in Brazil

Sandro could become the first player to win the Copa Libertadores and Champions League within a single European season.

It was in the periods of intense loneliness that self-doubt crept in. Sandro Raniere Guimarães Cordeiro would stare out of the window as the rickety bus, one of three the teenager had to take on the tedious two-hour journey to the centre of excellence each morning, weaved its way tortuously into Curitiba. Thoughts would drift to friends and family in distant Planaltina, a small town outside Brasilia 700 miles to the north, his focus distracted momentarily from the task ahead: impressing at the day's trials to forge himself a career.

Such was the 16-year-old's daily routine over two long months. Visiting scouts would scrutinise the youngsters on show, offering contracts to those who caught the eye. Atlético Paranaense warmed to the aggressive midfielder from the Minas Gerais province, only to have second thoughts. Contemporaries were snapped up, leaving Sandro behind. "I'd sit there asking myself: 'What am I doing here, in the middle of nowhere, miles from home? Why did I bother?'" he says. "But I knew I couldn't give up. I'd said I would only return when I had money to help my father and mother and, in the back of my mind, there was always my brother. I was living his dream, too. That gave me the strength never to give up."

That was a little over five years ago. Next week, Sandro will confront Real Madrid at the Santiago Bernabéu, travelling to Spain as a Brazil international, a Copa Libertadores winner and with his reputation at Tottenham Hotspur established by his smothering of Milan. Already he feels a steal at £6.5m, the 22-year-old following such talents as Alexandre Pato and Lúcio by progressing from Internacional Porto Alegre to Europe. Falcão, an icon at the Brazilian Inter then Roma, believes Sandro will be Brazil's regular No5, while Dunga considered him a future captain. The player describes the last few years as "a whirlwind" with each setback, and there have been some, brushed off: "I know I've already lived through the hardest part."

Sandro visited the Vale Resource Base at Northumberland Park Community School this week, spending time with a group of disabled children who, with the help of the Tottenham Hotspur Foundation, are competing for Haringey in a variety of disability sports in the Panathlon Challenge. The Brazilian was visibly moved by those he met, though his own story is similarly inspirational. It might not have been like this. Growing up in the small town of Riachinho, it had been his brother who was considered the prospect. Saymon was two years Sandro's senior and their father Juaci, a bricklayer, spent what money he could on boots and shin pads. Yet Saymon's dreams were to be dashed.

"In Brazil, a father's first present to his son is always a football," Sandro says. "Saymon and I would play in the streets in Riachinho, but the family concentrated on him, the eldest, and there were clubs chasing him. Then the doctors diagnosed a heart problem. They didn't know whether it was life-threatening, but it would be too dangerous for him to carry on playing. It was so hard on him, to give it all up… he was devastated and it affected the whole family. But seeing how he suffered was extra motivation for me. I told him: 'Don't worry, my brother. I'm going to do this for both of us. I will become the footballer we should both have been.'

"We moved nearer Brasilia so my brother could receive treatment and, even though we never had much money, my family never let me give up on my dream. My brother would work to buy me boots. My father would scrape together money for me to take the buses to Gama, a club in the city, but there were no prospects of making it there. They did not even pay expenses. I had to take a chance by leaving alone for the trialists' academy in Curitiba. The pocket money I got there paid for my transport to and from the centre. They supplied the kit, the manager gave me food and lodgings, and I had a phonecard to call my family. I suffered, miles from home, while everyone else was signed by clubs. But I knew it would happen.

"A small team called Astral eventually gave me an opportunity, but it wasn't until we played Grêmio in the São Paulo Cup that Internacional saw me. They invited me to Porto Alegre for a trial, but I had a groin injury when I got there and it took over six weeks to heal. Every day, the pressure grew. I knew the coaches were thinking: 'This kid's just wasting our time.' They'd not even seen me play, but my agent saved me, telling them to be patient. They didn't regret waiting. I was playing in their first team within two years."

Physically imposing and comfortable on the ball, Sandro oozed authority in the reserve team before graduating to the seniors at 18. The national set-up had already recognised his talent and he captained Brazil's Under-20s to success in the South American Youth Championships in Venezuela in February 2009. Seven months later he was a full international, the youngest of the 88 players called up by Dunga in his four-year stewardship. In Inter's first team the midfielder established a fearsome partnership with Pablo Guiñazú, a goateed, shaven-headed Argentinian whose nomadic career has spanned five countries. If the snarling Guiñazú was the destroyer, then Sandro was a more progressive force at his side, an interceptor rather than aggressor. "We were crazy mad dogs," he says. "On the pitch Pablo was frightening."

Internacional went unbeaten through the group stage of the 2010 Copa Libertadores with Spurs, their strategic partnership with the Brazilian club established, long since alerted to the dynamic midfielder emerging through the ranks. Agreement was reached last March for Sandro to transfer to White Hart Lane once Inter's Libertadores campaign had concluded. The player's room-mate Gonzalo Sorondo, previously of Crystal Palace and Charlton, would tell him about life in London. "He'd joke in English, though I never knew what he was on about," says Sandro. Harry Redknapp must have envisaged having him in his squad for pre-season. As it was, Inter would claim the trophy for the second time in four years, delaying Sandro's arrival until the end of August.

Their progress in the competition was as unlikely as Spurs' in the Champions League. A two-goal deficit was overturned against Banfield before the holders, Estudiantes, were eliminated – again on away goals – in the quarter‑finals. "Any meeting between a Brazilian side and a team from Argentina is unbelievable," Sandro says. "The noise, the tension, the passion … Everyone underestimated us. Estudiantes were sure they'd knock us out easily. São Paulo in the semis thought we'd roll over. But we would not give up. Halfway through the campaign I knew I was joining Spurs, so every game I played was potentially my last. But the dream went on and on. The final against Guadalajara was a chance to say goodbye in [the Estádio] Beira-Rio in front of 56,000, holding aloft that trophy. After that I could leave with my head held high.

"I'd watched how Tottenham had qualified for Europe, so I travelled to England looking forward to playing in the Premier League but also in the Champions League, the best competition in the world. But, when I got to London, the manager told me he hadn't put my name down in his European squad. I accepted it, but it was like a cold shower after everything that had happened: the Copa Libertadores, Brazil, the move to England. I was really disappointed, I'll confess, but I had to accept it.

"He told me I could still accompany the team on away trips in Europe to get to know everybody. But, ahead of the first game at Werder Bremen, the fitness trainer told me the day before the team was flying that I had to stay and work on my conditioning. My English was not good and I was confused because the manager had said I could go to watch the team. So I checked, with Heurelho Gomes and then my interpreter, and they came back with different answers. Something had got lost in translation. So I turned up at Stansted airport bright and early the next day and the man checking us in went down the list, saying: 'What is your name again? Sandro? Sandro … no, you're not down.' They had to leave me behind. It was so embarrassing."

He buries his head in his hands at the memory, though his painful adaptation period was not confined to an airport check-in lounge. Premier League starts were rare, his impact nullified by the jolt to the system of life in alien surroundings. Gomes was a support. So, too, were other compatriots, such as Chelsea's Ramires. Observers wondered if all this had come too soon, though it is testament to how swiftly Sandro has actually settled that Jermaine Jenas recently described him as a dressing‑room joker. Yet Redknapp needed more persuasion. The manager had explored the possibility of signing Phil Neville in the January window and, had he been prised from Everton, Sandro might not have made the revamped Champions League squad.

Tottenham will be grateful they gave him his chance. There had been only three domestic league starts when injuries demanded his inclusion against Milan but his displays against the Italians, cutting off the supply-line to Clarence Seedorf and suffocating the Rossoneri's menace, took the breath away. The physicality of football at this level suits him – he laughs off the gouge in his leg, now scabbed over, inflicted by a horrible Carlton Cole tackle in the derby with West Ham – and his energy and anticipation offer reassurance. Against Milan's wizened campaigners, his performance belied his tender years.

From Riachinho to Real, José Mourinho's Madrid await on Tuesday, the next step in a staggering journey. The Spanish, he says, "must not be feared". Cristiano Ronaldo, Xabi Alonso and Angel di María may be some of the world's best, "but Tottenham deserve to be where we are". "I'm still pinching myself that this is all real," he says. "But I gave everything. Looking back, all the sacrifices my family and I made, they were all worth it. I always believed, even if I didn't think things would happen so quickly. My brother is proud, too. He told me to be patient when I was not in the team at Tottenham, that my time would come. He's happy for me."

Saymon is in the process of applying for his passport back in Brazil but still hopes to experience an away tie in the Champions League. "It will not arrive in time for Madrid," Sandro says, "but he will have it when we play Barcelona [in the semi-finals]." That was said with a smile, but no one has ever won a Copa Libertadores and Champions League within the calendar of a single European season, and Sandro is a player in a hurry.

The Tottenham Hotspur Foundation aims to Create Opportunities that Change Lives for people in the community. Sandro appeared at the Vale School in Tottenham to support the charity's partnership with Panathlon.

Photos

More»[PICTURE SPECIAL] Arsenal 5-0 Chelsea

Wednesday April 24 2024Marcos Llorente’s wife wows in barely there swimsuit

Wednesday April 24 2024

Your Say